We all have them. You know… the passages about Jesus that we’d rather skip. They’re confusing, and confusion makes us scared. What if Jesus isn’t who we hope He is? Dr. Amy-Jill Levine, rides to our rescue in this episode, teaching us how to think through these difficult verses instead of blowing past them. (Spoiler Alert: Jesus IS who we hope He is … and more.) Come sit at the table and learn alongside Amy & Cheri!

(This page contains affiliate links. Your clicks and purchases help support Grit 'n' Grace at no extra charge to you.)

Recommended Resources

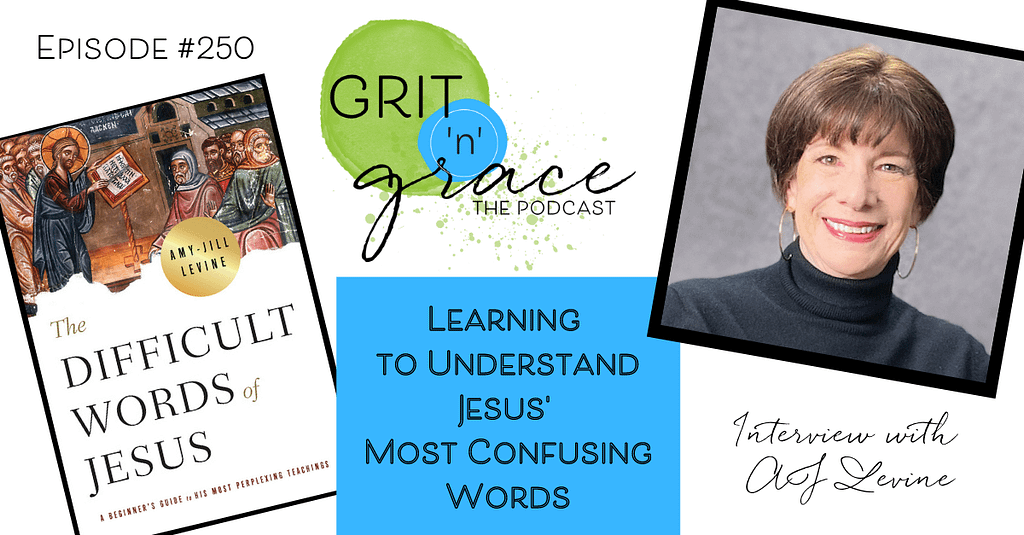

- Order Dr. Amy-Jill Levine’s book, The Difficult Words of Jesus: a Beginner’s Guide to His Most Perplexing Teachings

- Connect with Dr. Amy-Jill Levine on Facebook!

Featured Guest — Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Amy-Jill Levine is University Professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies, and Mary Jane Werthan Professor of Jewish Studies Emerita, at Vanderbilt Divinity School and College of Arts and Sciences.

An internationally renowned scholar and teacher, she is the author of numerous books including her latest release, The Difficult Words of Jesus: A Beginner’s Guide to His Most Perplexing Teachings. She is also the coeditor of the Jewish Annotated New Testament.

Professor Levine has done more than 500 programs for churches, clergy groups, and seminaries on the Bible, Christian-Jewish relations, and Religion, Gender, and Sexuality across the globe.

Transcript — scroll to read here (or download above)

****

Grit ‘n’ Grace — The Podcast

Episode #250: Learning to Understand Jesus’ Most Confusing Words

Cheri Gregory

We all have them.

Amy Carroll

You know, the passages about Jesus that – well, we’d rather skip.

Cheri Gregory

They’re confusing, and confusion makes us scared.

Amy Carroll

What if Jesus isn’t who we hope He is?

Cheri Gregory

Hmmm. Well today, Dr. Amy-Jill Levine rides to our rescue, teaching us how to think through these difficult verses instead of just blowing past them.

Amy Carroll

Spoiler alert: Jesus is who we hope He is, and even more.

Cheri Gregory

So, come sit at the table,

Amy Carroll

and learn alongside us.

Cheri Gregory

Well, this is Cheri Gregory –

Amy Carroll

– and I’m Amy Carroll –

Cheri Gregory

– and you’re listening to Grit’N’Grace: The Podcast that equips you to lose what you’re not, love who you are, and live your one life well.

Amy Carroll

Today we’re talking with Dr. Amy-Jill Levine, author of The Difficult Words of Jesus: A Beginner’s Guide to His Most Perplexing Teachings. AJ is a university professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies and Mary Jane Worden Professor of Jewish Studies Emeritus at Vanderbilt Divinity School and College of Arts and Sciences. An internationally renowned scholar and teacher, she is the author of numerous books and co-editor of the Jewish annotated New Testament. Professor Levine has done more than 500 programs for churches, clergy groups, and seminaries on the Bible, Christian-Jewish relations, and religion, gender, and sexuality across the globe.

Cheri Gregory

Jesus provided his disciples teachings for how to follow Torah, God’s word. He told them parables to help them discern questions of ethics and human nature. He offered them Beatitudes for comfort and encouragement.

Amy Carroll

But sometimes, Jesus spoke words that followers then and now have found difficult. He instructs disciples to hate members of their own families, to act as if they were slaves, and to sell their belongings and give to the poor.

Cheri Gregory

He restricts His mission. He speaks of damnation. He calls Jews the devil’s children.

Amy Carroll

In The Difficult Words of Jesus, Amy-Jill Levine shows how these difficult teachings would have sounded to the people who first heard them; how they’ve been understood over time; and how we might interpret them in the context of the Gospel of love and reconciliation.

Cheri Gregory

Additional components for a six week study include a DVD featuring Dr. Levine, and a comprehensive Leader Guide.

Amy Carroll

AJ, we’re so excited to have you with us today talking about just such a fascinating topic. Cheri and I’ve been very excited. Introduce us to your new Bible study, The Difficult Words of Jesus. So in what ways are these words of Jesus difficult?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

The reason we chose these particular sayings, like ‘Sell all you have and give to the poor, or you’ll be tossed into the outer darkness, where there’s wailing and gnashing of teeth.’ are just because people keep writing to me to say “I don’t understand this. And this doesn’t sound like the Jesus I learned about in Sunday school. And what do these things mean? And what kind of God are we talking about here?” So I thought, ‘Yeah, these things disturb me as well. And it was about time that we actually wrestled with some of this material, rather than saying, “Oh, that’s just Jesus being Jesus.” and moving on to the easier stuff. So I had fun writing it. And so far the people who have contacted me have said “Finally, somebody is actually talking about these difficult things. Good.”

Amy Carroll

Yes, fantastic. We want to know.

Cheri Gregory

I love the subtitle of your book: A Beginner’s Guide to His Most Perplexing Teachings. I remember when I was younger, my mother was in charge of the youth classes at our church, there are many stories she would omit. Even if they were in the pre-printed lessons, you know, she thought they were inappropriate for children. And so I’m excited that you’re tackling these.

Now, you start the introduction of your book by writing that the role of a religious community is not to be like sheep, despite all the sheep and shepherd metaphors found in Scripture. So why is it important to wrestle with passages that confuse us rather than simply take them as we’ve been taught in the past? Or in my case, I wasn’t taught, and I was basically taught to skip them. So why should we wrestle with them?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Well, because they’re in there for a purpose. If the religious communities that gave us our Bibles did not think these statements were important, they would not have written them down, right. I think that little children in Christian churches should have better career aspirations than wanting to grow up to be a sheep, baa baa. You know what, we are created as human beings with brains and we ought to use them. There’s a great deal of material in the Jesus tradition that requires interpretation. Parables require interpretation, right? Those who have ears to hear. And sometimes Jesus particularly – and Mark says to the disciples, are you also without understanding? Come on, guys. Work at this.

And I think if we stop being sheep and stop letting other people tell us what to believe, but engage the text for ourselves and look at what people from different perspectives have said about it so we can make up our own minds but be informed in the process. I think that’s more faithful Bible reading. I think it’s better pastorally for the individual. And I think it’s also a better way of forming community. Because if community is formed by ‘Here’s what the master told us, or here’s what the pastor told us, and we don’t have any opinions on our own,’ that’s not community. That’s just a bunch of objects being manipulated.

Amy Carroll

Oh, wow. That is so, so powerful.

So please explain what you mean when you say that the Bible is less a book of answers than a book that helps us to ask the right questions. Fascinating statement.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

So there are people who have told me that they think of the Bible like those magic eight ball things where you just, you know, you ask it a question, you turn it over, and you get an answer; or that you just open the Bible at random, and God will tell you what you need to know, except you usually wind up, you know, opening up in the book of Job, which tends not to be all that optimistic. And that’s this making the Bible like some sort of magic book. And it’s also kind of boxing up God because it – God can’t be free. And it’s – finally, it’s forcing us to say, well, if the Bible has all the answers, then clearly we’re living at the beginning of the second century, when the last New Testament books were written, right? And why should we be playing first century Bible? And there are certain things to which the Bible does not give us easy answers.

But it helps us ask the right questions, so that once we can figure out what the right questions, then we’re in a better position to say, oh, if you happen to be suffering from COVID, and you have food insecurity, and there’s not enough money in the bank, and you’ve got two kids who are crying because they’re hungry, the answers that you might find might not be the same answers as somebody who’s, you know, who’s got a multi-million dollar mansion and is perfectly healthy. But the text says, ‘Well, what are the right questions? Well, what are our responsibilities to people who are suffering? How do we understand suffering in a world where we believe in a just God?’ Those are the right questions to ask. That’s just the soundbite version. I mean, it’s more complicated than that.

Cheri Gregory

Of course. But you know, I’m gonna go back to something you said a few minutes ago. ‘Come on, guys work at this.’ And some of us, I’ll raise my hand here, at least – I feel – I’m not saying it was 100% true, but I feel like I got the gold stars growing up for giving right answers. I did not get the gold stars for asking good questions. In fact, I got in trouble for asking too many questions.

So I’m going to take a little tangent here. What about us? And I’ll even say what about us girls, that’s grown up, girls known as women who might not be as used to asking questions and might have, might be used to the rewards of being the the ones who had the pat, quick answer. Amy?

Amy Carroll

No, jazz hands. Yeah, I want to know what AJ has to say.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

I get that. But you know, they’re not mutually exclusive. You can be the smartest one in class in terms of basic book learning, like you memorize stuff. But that doesn’t stop you from asking questions, you can have both. And for me, when I was a kid, I was encouraged to ask questions. When I would come home from school. My mother would say to me, “Did you ask any good questions today? What interested you? What did you think was peculiar? What bothered you?” When we would read books together – because my mother was big into reading – so even when she would be reading the bedtime story, “Do you have any questions about this? What do you think about Cinderella?” I think she should have spoken up a little bit. “How about those mice? What would you do if you’re one of the ugly stepsisters?” I mean, it’s just – I was raised to ask questions. I was raised so that my curiosity was nurtured rather than shut down.

And I find, too often, for people who go to religious education in whatever form Sunday school, vacation Bible school, catechism, Hebrew school, whatever you call it, particularly in Christian context, kids are not encouraged to ask questions, because that might get them into trouble. Oh, goodness. If you stifle the child’s imagination, or if you say there are some questions that you simply can’t ask, then the child is either going to feel frustrated or feel guilty. And that’s not good for anybody.

Amy Carroll

Oh, my gosh. I just can’t even. I’ve got some reparenting to do. I’ve got some reparenting to do for real. And listen, we’ve got kids in their 20s who are now asking questions that they should have asked his children, and we would have less wrestling with their faith. I mean, let’s be honest, I think that we’re seeing that in that generation. So well said. Young mamas, listen, for those of us that have adult sons and daughters, we got some reparenting to do. So, awesome.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Can I say one more thing about that?

Cheri Gregory

Absolutely.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

What I find in the classroom – so if you’re thinking about young parents with young children will eventually they’re going to grow up and they’re probably going to go to college, or many of them will, and they’ll get into a Bible classroom. And they’ll see things that their Sunday school teachers and their youth leaders kept away from them and they will be resentful as all get out. Yes. So if you want to keep your kids in your particular religious tradition, be honest with them right from the beginning.

Amy Carroll

So well said.

Cheri Gregory

What are some things that a 21st century reader should keep in mind when trying to get to the root of a message originally written to a first century reader?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

It’s a double question. Historians can get a pretty good sense of what the takeaway would have been from the various things that Jesus said; it’s very difficult to determine what Jesus intended, right, because it can’t get into His head. But we can get a pretty good sense of what message people would have taken because we know something about the context, we know something about the other things that people were exposed to, we know how they understood their own scripture, we know pretty much how they understood living in Galilee, or Judea, under Roman rule, we know about their their sense of social justice because we know how they’re reading Deuteronomy, for example.

So we can get a pretty good sense of the takeaway. But we can’t stop there. Because if the text is to be a living document, right, if the text is still speaking, which it needs to do for Judaism and Christianity to continue, then it cannot only mean what it meant in the first century, it has to have additional meaning. In the Christian tradition, that’s the job of the Holy Spirit, right? The Gospel of John, Jesus says, I have to ascend so that the the Comforter, the spirit, can descend, and the Spirit then guide you, right sort of gives you pointers on on how you proceed. In the synagogue, there’s the ongoing concern of the community. So the community addresses this material, we have always interpreted this text. So it doesn’t remain a first century text. It’s also a 21st century text. But you have to make appropriate adjustments.

Amy Carroll

And I want to ask another off the road question, because I’ve been hearing a lot – I’ve been listening a lot to Kristen Dumay talk about how our history has affected our interpretation of Scripture. Do you think it’s valuable to look at how other cultural context other countries, other ethnic groups, how they interpret Scripture?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Absolutely. Because nobody has a lock on the complete meaning. And I know that from being in the classroom. Can I tell a classroom story?

Both

Yes, please.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

So I’m teaching a seminar on the Gospel of Luke. And we’re looking at the parable of the prodigal son, which I expect your your listeners will know, right? So the younger brother goes off, and he blows all his money, and then he has to go home. So I stopped. And I said to my students, “What went wrong with this young man that he’s stuck in some foreign land working for a pig farmer?” And the answers were culturally contingent. So all the Americans in the class, that financially responsibility, his parents didn’t teach him the value of money. A number of people said he was the younger child, and he was spoiled. So there was no responsibility. It was all like personal responsibility stuff.

The student from Australia said the problem was that he left home, because in Australia, if you leave home, you really leave home, right? Because you can’t get back there. Easy enough. And I thought that was a great answer. And I heard from a friend of mine, Mark Allen Powell, who teaches at the Lutheran Seminary in Ohio, he went to Russia to Moscow, and he asked the Lutherans in Moscow, what do you think went wrong with this kid, and they said, a famine hit the land. And Americans didn’t notice it at all. So I thought, great, I’ve got my multicultural readings, I’ve got my Australian readings, I’ve got my Russian readings. And I said, well, maybe it’s the famine.

And I had a student in the class from Kenya, who said, no, no, no, that’s not the problem at all. And I said, “What’s the problem?” She said, “Nobody gave him anything.” And all these statements are part of the parable. But people from different cultures overlooked things. So people want to land of plenty overlook the famine. People who have easy transportation and can get to their parents are not far from home, don’t notice the going away, and people who have you know, easy internet access, or a huge group of friends, and who don’t know what it’s like to be alone, don’t notice that other reading.

So reading from multicultural perspectives, absolutely. And we can even see that in our own American context. If you come out of an environment of slavery, you’re going to notice those slaves in the text a lot more than if you come from an environment where slavery is not part of your own personal history.

Amy Carroll

Fascinating. Okay, I’m inserting my own question here, because I got to hear you talk about it.

Several years ago, when Cheri and I were writing our book, God bossed me around and made me write a chapter on the Canaanite woman. And I told Him that we shouldn’t do that because it makes him look really bad. Cheri and I will talk more about this. But you know, it is one of these difficult passages with Jesus like, that doesn’t sound like Jesus. Because He says, “I was only sent to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. It is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” I mean, that sounds racist. It sounds like we Gentiles shouldn’t have a piece of Him at all. What was that all about?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Well, how much time do we have? I mean, this is why she gets a whole chapter. It’s a fascinating story. I love this story. It’s actually Matthew’s rewrite of Mark chapter 7. Same story, but Matthew has actually lengthened it in Mark. She’s a Syrophoenician woman. So she’s kind of upperclass, hoity toity, in Matthew. She’s a Canaanite, and Matthew has already given us to Canaanite women in the genealogy, at least two Canaanite women, Tamar and Rahab. Two women, the first two women who are mentioned in the New Testament who wind up getting with the program, when the men with whom they’re paired are a little slow on the uptake.

So as soon as Matthew mentions that she’s a Canaanite woman, I know she’s going to succeed. I know the men with whom she’s paired are going to be a little bit slow. But I also know that they have a learning curve. And I think that’s terrific. Why should Jesus not be able to learn? I mean, Luke suggests that He, after his temple incident, where it’s the original screenplay to Home Alone, like Mary and Joseph specimen, the temple and have to go back and get him. And He goes back in and he grows in wisdom. So of course he does. He’s a human being.

And one of the things that make human beings interesting is that we can learn from others. And if one takes Jesus as God, then God is in communication with us. And God enjoys being in communication with us, this whole point of the Old Testament, and you can argue with God, and God can actually change God’s mind, right? God says, “I’m gonna wipe out Sodom and Gomorrah.” Abraham says, “Yeah, what if there are 50 righteous people there, You can have a chat.” God says, “I think I’m going to wipe out the Israelites.” Like, you know, I did the 10 plagues, I parted the Red Sea, I got them out of slavery. Now they’re on dry land, and they’re complaining about the food. I’ve had it with these people. And Moses says, it won’t look nice, right? You did all these miracles. The nations will talk.

I mean, Job can chat with God. So why can’t we try to convince God to do something else? Jesus had said back in Matthew chapter 10, right at the beginning of the mission discourse, that His disciples should not go to the Gentiles either. Why? Because the Jews get first dibs. And that would make sense. The nations are to be blessed through Abraham. So it would make sense that the children of Abraham will be part of that blessing to the other nations.

And then what Matthew does at the end of the gospel in the Great Commission, Jesus says, “Now all authority has been given to me.” Because he didn’t have it before. And therefore, because there’s a change in my status, there’s a change in the mission, go make disciples of all the Gentiles, and the Canaanite woman sets up that Gentile mission. There’s a whole lot more to say about her. I think she – I think they’re both fabulous. Jesus, He doesn’t want to do it. And she convinces Him. Which is a – it’s like a lament song, right? It’s like saying, My God, My God, why have you forsaken me? Psalm 22. It’s a good lament song. So what do you do, you say help me. you don’t get an answer. You say help me again. And then you say, well, you know, you helped Israel before. And if you help me, I will praise you. Come on, get with the program. So it makes sense in a first century context.

And what makes even more sense, is that there’s a convention at the time, it’s a literary convention, you find the same story in Roman history, you find it in Jewish history of a very, very important person who was approached by a person who has no social capital whatsoever. And the important person doesn’t want to deal with with that other person. And basically, and it’s often a woman, shuts her down, says you’re not, you know, you’re not at my table, I don’t want to have anything to do with you, go ask somebody else. And that person with no social capital comes up with an extremely clever word. And because of that clever word, the person in effect gets down off his high horse. And that tells people who have no power, you do have power, you have words, you – if you kneel in front of somebody, which is what this Canaanite woman does, she’s stopping Jesus in His tracks, she’s holding her ground.

So it tells people who have little power, you have power. And here’s how you do it. You stay in. And if somebody insults you, you don’t turn around in insult back. Right? So Jesus calls this woman a dog. She could have said something worse to him. She doesn’t. She’s fine, call me a dog. But even dogs are entitled, and it tells people who have power. And here are the disciples who were there in Matthew’s version of the story. If somebody comes to you, and you think you’re too important to deal with him wrong. Jesus learned. You’ve got to learn from Jesus. And Jesus provides the model of somebody who, you know, you’re not part of my job description right now. But you’re absolutely right. You deserve a hearing as well. It’s a brilliant listen.

Amy Carroll

It’s so fascinating. I learned from you so much. But the end of the story – spoiler alert – is that Jesus does exactly what the woman asked Him to do. And I just think He’s so delighted in her faith, and it’s a happy story.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Just thinking – in Mark, Jesus praises her because of her word. Like lady, great answer. Matthew likes to talk about faith. So Matthew changes it to faith. I think it’s both. And there’s a part of me that thinks you know, great is your faith, because you knew I could work this miracle; but also great is your faith because you had faith in yourself, that you persevered. And it’s like the sermon on the mount where Jesus says, you know, if you get slapped on one cheek, don’t hit back. But don’t cower either, stay in the game. That’s what she does. She models the Sermon on the Mount.

Cheri Gregory

I love it. I had never noticed that He praised a woman for speaking. So often women are the butt of jokes for speaking up. So I like that too.

You were mentioning power, the power dynamic. And so another topic closely related, there is slavery. It’s a sensitive topic, and it makes us uncomfortable to talk about it or think about it, and, not but, the term slave appears more than 100 times in the New Testament. So what can we learn from the Bible about the moral aspects of slavery?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

That’s one of those really good questions that we need to ask. And because slaves show up so often, we really need to pay attention to how that slavery language functions, we can’t ignore it. Part of our problem – and looking at this as translation. So how many people think about Mary’s saying, you know, I am the handmaid of the Lord, behold, the handmaiden of the Lord, but the Greek is slave. But the other thing is the only people in the Bible who self identify as slaves – I mean, Moses talks about being a slave of God, Paul talks about being a slave of Christ, Mary talks about being a slave of God, the only people who use that language of free people.

So on the one hand, that slavery language says, My master is God, and therefore I can have no other human master, and that gives me ultimate freedom. On the other hand, if you’re already a slave, in what sense can you be a slave of God, if you’re also serving a human being? Because Jesus says, You can’t serve two masters. He’s talking about money and God, sure, but it raises that other question.

And in antiquity, it was a huge question, because there were slaves who joined these fellowships in the name of Jesus, but their masters were pagan. And that was really awful for them, because the master expected the slave to be part of the Masters religious identity, and the slave has this different identity. And what happens if you’re a Christian slave owner with a Christian slave, because we know that was happening. Why didn’t they think about gee, if we’re all in the image and likeness of God, why are we keeping slaves? So the very notion of slavery here says, Well, if it happens in the Bible, then we ought to pay attention to it in our own culture, and pay attention to its legacy. Whether the term is usable or not depends upon the individual Christian in the individual church.

So I know a number of people who were, you know, they’re people of privilege in a variety of ways, whether racially or ethnically or economically, or in terms of education, they do really, really well. And they like that slave language, because it reminds them to be humble, it reminds them that they’re not the one in charge, that God’s the one in charge, it reminds them that they’re supposed to engage in service to others. But I also know a lot of other people, and particularly a number of my Black friends and folks who are coming out of the Black church who say, you cannot talk about being a slave of God, the word is simply to compromise. And the only people who would be comfortable using that term are people who don’t know what it’s like to be a slave in the first place. And that’s where people in congregations need to talk with each other, because sometimes words are still usable. And sometimes we need to find better metaphors.

Amy Carroll

How would you replace that word?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

If I’m reading the Bible, I’d want to keep it there. Because I don’t like taking razor blades and taking stuff out of the Bible. Use it to raise those good questions about what do we do now. Does it remind us of the idea that some people are still in effect enslaved, because human trafficking is continuing, and there are still some countries where slavery is legal? Do we think about what it means to be a slave to God, if we are free, to think about God is our master and then we can speak about what enslaves us? Because along with real slavery, like people owning other people, there are people who are enslaved to drugs, or people who are enslaved to power or to beauty, and what does it mean to be set free from that? So if you talk about being a slave, you also have to talk about what it means to be free. I love that variety of places we can go here, but it’s hard. And it should be hard.

Amy Carroll

But you know, what I also hear and what you just said is this gives a place for the Black church to speak to the white church, because they have experienced, like a physical being freed from slavery. So they have an insight to what that means that the white church does not and so they can teach us. I love that.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

There’s that, and you can even extend it, because for Jews who were still celebrating the Passover, the Exodus from Egypt, that’s that’s the marker of Israel’s identity. And for Christians who take their Old Testament seriously, we are all somehow descended from slaves because the people of God were enslaved. So what then do we learn from that? The Torah, the Pentateuch tells us that we were slaves in Egypt. And you know, we knew what that was like. So why should you welcome the stranger, because you were slaves in Egypt and you knew what it was like not to be welcomed. Can you take the next step and say, well, you were slaves in Egypt, so therefore don’t hold slaves. That’s exactly what the Torah does, so that by the time you get to the end of Deuteronomy, at least Israelites can’t hold other Israelites enslaved, they didn’t extend that to Gentiles. But that would have been the next step.

And then we watch to say, well, how do we take what the Bible teaches us? And can we go to that next step and make sure that everybody is free? Or do we regress and say, oh, no, we’re just going to own Christian slaves? How do we move? How do we learn from the Bible? How do we learn from our experiences, including the Exodus?

Amy Carroll

Excellent. The last chapter of the difficult words of Jesus takes a look at a verse that can cause some issues in our world today. Can you share just a little bit about the final verse that you examine?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Well, it’s a verse, but it’s pretty much the entire Gospel of John, which is how John talks about the Jews. So in John chapter 8, Jesus talking to a group of Jews who were identified by John as Jews say, you are children of your father, the devil, and you always do your father’s desires.

And what has happened over time is the view developed that Jews had horns. I have twice – I’m Jewish, I have twice been asked by nice Methodist ladies, once in North Carolina, where I did my graduate work, and what’s now in Tennessee, where I live now, where did I have my horns removed. And I said, Jews don’t have horns. And they were delighted to hear that, because they thought from the Gospel of John and for Michelangelo’s statue of Moses, which has horns, is based on a translation problem, that Jews actually had horns. I don’t think they were anti-Semitic, I think they were just ignorant.

And I was actually glad they asked the question, because then we can move on from there. But I have seen in my many years, I’m old, fabulous. By the way, I have seen so much anti-Semitism, and not just by, you know, neo-Nazis, I’ve seen it expressed by well-meaning Christians who do not realize how harmful some of the statements they make are. Because we sometimes say things that are so offensive, and we simply don’t realize how offensive they are. So how do we make sure that the gospel of love does not sound like a gospel of hate? I think it’s the gospel of love. And I would like my Christian friends to think the same thing and not say something that would deform the text.

Amy Carroll

So what final words do you have for our listeners about grappling with the difficult words of Jesus?

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine

Well, the church considers itself to be grafted on to Israel. That’s Paul’s image of this big olive tree. Gentiles get grafted on. But the term Israel traditionally means to wrestle with God. So how do you do that? You wrestle with the text. And if you think God is telling you something in the text that you don’t find to be morally appropriate, then you wrestle with it the same way that Abraham wrestled with God and Moses wrestled with God and Job wrestled with God. It’s the – Psalms wrestle with God, it’s what you do. And you make sure that when you interpret that it leads to love rather than to hate, and it leads to acts of kindness rather than to malevolence. And you continue to ask questions. And if you get an answer, that’s great, but recognize that the answer is only partial, because other people will answer the same question differently. And that’s why Jews insist on doing things in a community, and that’s why Jesus insists that He’s present where two or three are gathered in His name, because that way, you can have a conversation.

Cheri Gregory

Friends, we so appreciate you tuning in each and every week.

Amy Carroll

And we’re especially grateful to AJ Levine, author of The Difficult Words of Jesus: A Beginner’s Guide to His Most Perplexing Teachings, and her publisher, Abingdon Press for making this week’s episode of Grit’N’Grace possible.

Cheri Gregory

Check out this episode’s web page at gritngracethepodcast.com/episode250. There you’ll find this week’s transcript and a link to AJ’s book, The Difficult Words of Jesus: A Beginner’s Guide to His Most Perplexing Teachings.

Amy Carroll

Be sure to join us next week – we’ll be talking with Lily Taylor, author of Unconfined: Lessons from Prison and the Journey of Being Set Free.

Cheri Gregory

For today, grow your grit –

Amy Carroll

embrace God’s grace,

Cheri Gregory

and as God reveals the next step to live your one life well,

Amy Carroll

we’ll be cheering you on!

Cheri Gregory

So –

Both

take it!